DIT: Four Fat-Burning Facts About the Effects of Calories, Macros + Meal Timing on the Thermogenic Effects of Foods

Well, today's SuppVersity article will not be able to answer all of these questions in a "once and for all" fashion, but being based on the latest systematic review by Quatela et al. (2016), it will still give you a good overview of the individual effects of differing energy intakes, macronutrient compositions, and eating patterns of meals on what scientists call your DIT, i.e. your "diet-induced thermogenesis" (DIT) in response to a std. meal.

While fasting will obviously not trigger DIT, it relates to the effects of meal frequency on DIT

Higher energy intake increased DIT; in a mixed model meta-regression, for every 100 kJ increase in energy intake, DIT increased by 1.1 kJ/h (p < 0.001 | Quatela. 2016).

There's, for example, the 1990 study by Kinabo and Durnin who found no effect of the macronutrient composition of the test meals they served either high-carbohydrate-low-fat (HCLF) with 70%, 19% and 11% of the energy content from carbohydrate, fat and protein, respectively, or a low-carbohydrate-high–fat (LCHF) with 24%, 65% and 11% to sixteen adult, non–obese female subjects.

Meals with a high protein or carbohydrate content had a higher DIT than high fat, although this effect was not always significant (Quatela. 2016).

The next take home message takes us back to my claim from the introduction: you all will have heard about the beneficial metabolic effects of high protein breakfasts. And in contrast to what the take home message says about carbohydrates, the evidence that high(er) protein intakes yield higher levels of diet-induced thermogenesis has been found consistently (see green lines in the Table 1) .

What should also be mentioned, though, is the fact that there's ZERO evidence to the opposite, i.e. an acute increase in thermogenesis to high fat intakes, when the meal size / energy content is standardized and the protein content is kept the same... and no, the study by Riggs et al. (2007) is not an example that this statement was wrong. After all, the "high fat" group in Riggs' study also received increased amounts of protein. The effects on DIT the scientists observed may thus well be ascribed to the extra 10% protein, not to the increased fat and/or reduced carb content.

You better don't starve yourself either! While the previous red box has thought you about the ill consequences being obese will have on your body's ability to burn off extra calories, the previously mentioned study by Riggs et al. shows that being too thin, i.e. underweight (starved), appears to have the same effect. In their study a higher protein intake lead to an increase in DIT only in the normal- yet not in the under- and overweight women; and that the exact same lack of thermogenesis can be observed in weight-reduced formerly obese subjects has been observed by Schutz et al. (1894) more than 40 years ago.

Simply distinguishing between calories and macros, alone, however, is not sufficient to predict the real-world DIT effect of a given meal. This (hopefully) unsurprising revelation takes us right to the last two take home messages that relate to the DIT effect of certain micronutrients and the importance of meal frequency.Meals with medium chain triglycerides, and meals high in PUFA had a significantly higher DIT than other fats (meta-analysis, p = 0.002 | Quatela. 2016).

Yes, it is true MCT oils are not just rapidly metabolized, there's also good evidence that they can increase the diet-induced thermogenesis in mouse and, more importantly, man (Kasai. 2002a,b; Clegg. 2013 | discussed => here).

|

| Figure 2: The thermogenic effect of a meal does also depend on the type of fat in it (Casas-Agustench. 2009) |

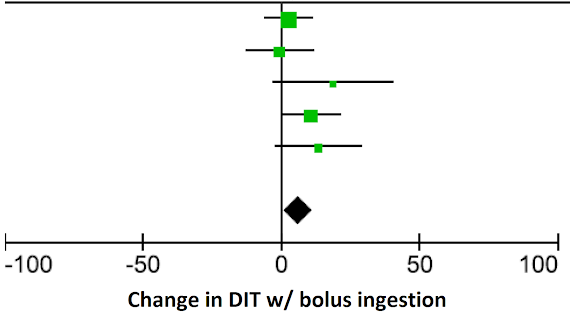

Consuming a meal as a single bolus eating event compared to multiple small meals or snacks was associated with a significantly higher DIT (meta-analysis, p = 0.02 | Quatela. 2016).

The last of our four take home messages is one you have read in previous SuppVersity articles about the advantages and disadvantages of fasting and/or a lower meal frequency, before. If you compare the effects of consuming a standardized meal as a bolus event versus splitting the same meal into two (Kinabo. 1990), three (Vaz. 1995), four (Allirot. 2013) or six (Tai. 1991) smaller equal meals or snacks to be consumed throughout the morning, the bolus administration will always produce the highest thermogenic response.

|

| Figure 3: Mean differences in DIT between bolus vs. frequent smaller meals (e.g. snacking | Quatela. 2016) |

|

| The degree of processing will likewise affect the thermogenic response to food (Barr. 2010). |

With that being said, I cannot let you go without reminding you that neither the extra 10kcal/h you expend if you add another 1000kcal to your meal nor 17% increase in DIT you can get from increasing a meal's protein content will strip an inch off your waist or decrease your body fat percentage by 0.1% - and comprehensive evidence on the long-term effects is still warranted (for meal frequency there's some; the same goes for high protein). Optimizing your DIT should thus be only one (and not the most important) strategy in your dieting toolbox | Comment.

- Barr, Sadie B., and Jonathan C. Wright. "Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure." Food & nutrition research 54 (2010).

- Casas-Agustench, Patricia, et al. "Acute effects of three high-fat meals with different fat saturations on energy expenditure, substrate oxidation and satiety." Clinical Nutrition 28.1 (2009): 39-45.

- Clegg, Miriam E., Mana Golsorkhi, and C. Jeya Henry. "Combined medium-chain triglyceride and chilli feeding increases diet-induced thermogenesis in normal-weight humans." European journal of nutrition 52.6 (2013): 1579-1585.

- Kasai, Michio, et al. "Comparison of diet-induced thermogenesis of foods containing medium-versus long-chain triacylglycerols." Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 48.6 (2002a): 536-540.

- Kasai, Michio, et al. "Comparison of diet-induced thermogenesis of foods containing medium-versus long-chain triacylglycerols." Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 48.6 (2002b): 536-540.

- Kinabo, J. L., and J. V. G. A. Durnin. "Thermic effect of food in man: effect of meal composition, and energy content." British Journal of Nutrition 64.01 (1990): 37-44.

- Kinabo, J. L., and J. V. Durnin. "Effect of meal frequency on the thermic effect of food in women." European journal of clinical nutrition 44.5 (1990): 389-395.

- Hill, James O., et al. "Meal size and thermic response to food in male subjects as a function of maximum aerobic capacity." Metabolism 33.8 (1984): 743-749.

- Piers, L. S., et al. "The influence of the type of dietary fat on postprandial fat oxidation rates: monounsaturated (olive oil) vs saturated fat (cream)." International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 26.6 (2002): 814-821.

- Quatela, Angelica, et al. "The Energy Content and Composition of Meals Consumed after an Overnight Fast and Their Effects on Diet Induced Thermogenesis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions." Nutrients 8.11 (2016): 670.

- Riggs, Amy Jo, Barry D. White, and Sareen S. Gropper. "Changes in energy expenditure associated with ingestion of high protein, high fat versus high protein, low fat meals among underweight, normal weight, and overweight females." Nutrition journal 6.1 (2007): 1.

- Schutz, Yves, et al. "Decreased glucose-induced thermogenesis after weight loss in obese subjects: a predisposing factor for relapse of obesity?." The American journal of clinical nutrition 39.3 (1984): 380-387.

- Tai, Mary M., Peter Castillo, and F. Xavier Pi-Sunyer. "Meal size and frequency: effect on the thermic effect of food." The American journal of clinical nutrition 54.5 (1991): 783-787.

- Thyfault, JOHN P., et al. "Postprandial metabolism in resistance-trained versus sedentary males." Medicine and science in sports and exercise 36.4 (2004): 709-716.

- Vaz, Mario, et al. "Postprandial sympatho-adrenal activity: its relation to metabolic and cardiovascular events and to changes in meal frequency." Clinical Science 89.4 (1995): 349-357.