Sprint & Strength Training - A Dynamic Duo For Synergistic Effects: Increased Fitness, Power & Endurance With HIIT + Heavy Lifting in Recreationally Active College Students

|

| Sprinting allowed: Adding two high intensity sprinting interval sessions to a basic weight lifting template entails nothing, but benefits. |

You can learn more about High Intensity Interval Training at the SuppVersity

- the concurrent training group (CT) trained on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday with half of the group strength training on Monday and Thursday, while the others performed strength training on Tuesday and Friday, the high intensity sprints were always performed on the other two days

- the strength training, only, group (ST) completed a general five-min warm-up on a cycle ergometer, before they did back squats, bench presses, leg extensions, leg curls, pull-downs, and shoulder presses in the four to six repetition range (i.e., 85 % 1RM) w/ 2 min rest intervals on two days of the week, only

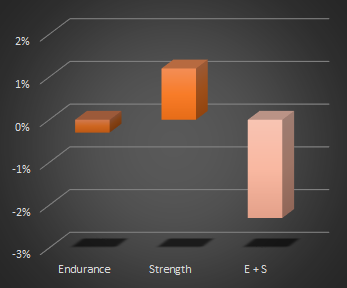

If you take a look at the data in Figure 1 it's plain to see that the "no sprinting", strength only group did not record additional strength gains.

|

| Figure 1: Changes in performance parameters after 6 and 12 weeks (Cantrell. 2014) |

|

| Figure 2: VO2Max before, during and after the intervention (Cantrell. 2014) |

A low VO2max and correspondingly messed up fitness status, on the other hand, has been linked insulin resistance and fasting hyperglycaemia (Ghouri. 2013), high blood pressure (Emaus. 2011), a loss of cerebral white matter integrity (Marks. 2011), lower blood viscosity and increased cardiovascular disease risk (Lee. 2012).

It is thus not surprising that Lee et al. write in their review of the ,ortality trends in the general population and the importance of cardiorespiratory fitnesst that the latter is "at least as important as the traditional risk factors, and is often more strongly associated with mortality." (Lee. 2010)

Identical gains on the bench, improved power and a fitness bonus - what more can you ask for? Well, I guess I know what you are probably asking for, now. Fat loss! Well, in the study at hand, the researchers didn't observe any changes in body composition.

The latter may be a results of the fact that the participants were already pretty fit (that's also likely to be the reason that their VO2 max suffered, when all the exercise they did was heavy lifting twice a week). Other studies, such as Hakkinen et al. (2003), Glowacki et al. (2004) and Mikkola et al. (2012) did observe improvements in body composition - pretty significant ones, in fact.

So, if an 11% greater increase in endurance capacity (based on time to exhaustion; not shown in any figure), 7% higher increases in peak and 10% greater increases in average power are not enough to motivate you to spend a couple of minutes sprinting along the track / on the treadmill twice a week, the fat loss results of the healthy male subjects in the previously cited study by Mikkola et al. (see Figure 3) could be the incentive you need to finally break out of your comfort = no results zone - if you wanted to copy this regimen you'd have to add another 30min of steady state cardio before or after your HIIT sessions.

Reference:The latter may be a results of the fact that the participants were already pretty fit (that's also likely to be the reason that their VO2 max suffered, when all the exercise they did was heavy lifting twice a week). Other studies, such as Hakkinen et al. (2003), Glowacki et al. (2004) and Mikkola et al. (2012) did observe improvements in body composition - pretty significant ones, in fact.

|

| Figure 3: Changes in body fat (%) in the Mikkola study (Mikkola. 2012) |

- Cantrell, Gregory S., et al. "Maximal strength, power, and aerobic endurance adaptations to concurrent strength and sprint interval training." European journal of applied physiology (2014): 1-9.

- Cataldo, Angelo, et al. "Relationship between maximal fat oxidation and oxygen uptake: comparison between type 2 diabetes patients and healthy sedentary subjects." Journal of Biological Research-Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale 87.1 (2014).

- Emaus, Aina, et al. "Blood pressure, cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass: Results from the Tromsø Activity Study." Norsk epidemiologi 20.2 (2011).

- Ghouri, N., et al. "Lower cardiorespiratory fitness contributes to increased insulin resistance and fasting glycaemia in middle-aged South Asian compared with European men living in the UK." Diabetologia 56.10 (2013): 2238-2249.

- Lee, Duck-chul, et al. "Review: Mortality trends in the general population: the importance of cardiorespiratory fitness." Journal of Psychopharmacology 24.4 suppl (2010): 27-35.

- Lee, Duck-chul, et al. "Changes in fitness and fatness on the development of cardiovascular disease risk factorshypertension, metabolic syndrome, and hypercholesterolemia." Journal of the American College of Cardiology 59.7 (2012): 665-672.

- Marks, B. L., et al. "Aerobic fitness and obesity: relationship to cerebral white matter integrity in the brain of active and sedentary older adults." British journal of sports medicine 45.15 (2011): 1208-1215.

- Mikkola, J., et al. "Neuromuscular and cardiovascular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training in untrained men." International journal of sports medicine 33.09 (2012): 702-710.

- Singhvi, Ajay, et al. "Aerobic Fitness and Glycemic Variability in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes." Endocrine Practice (2014): 1-18.